Abstract:

Recently, two important syntheses on European jazz have been published: Eurojazzland:Jazz and European Sources, Dynamics, and Contexts by Luca Cerchiari, Laurent Cugny and Franz Kerschbaumer (2012); and Jazz behind the Iron Curtain by Gertrud Pickhan and Rüdiger Ritter (2009). The publications show the division of European jazz scenes between east and west, and they also deal with the methodological inconsistencies in jazz research and analysis which have precluded an integrated chronological approach to jazz events, personalities and styles. Progress, although regarded as the foremost quality, is not the only value in jazz development; and, especially since the death of Miles Davis, it has become a rather vague one. On the other hand, for the further development of jazz it is essential to respect the genre‘s traditions which foster jazz personalities to preserve the older jazz styles; however, for the future of jazz, qualities such as creative musicianship, innovation, jazz promotion and education, advocacy and popularization are equally important. These values are demonstrated by such personalities as the Slovak jazz singer Peter Lipa (b.1943) and the Czech-Slovak- Australian jazz pianist Viktor Zappner (b.1936).

European Jazz, Research, Methods and Results

In the last four years, two important publications on European jazz were published: Eurojazzland. Jazz and European Sources, Dynamics, and Contexts by Luca Cerchiari, Laurent Cugny and Franz Kerschbaumer (2012); and Jazz behind the Iron Curtain by Gertrud Pickhan and Rüdiger Ritter (2009). While the authors of Eurojazzland adopted an inductive-comparative approach, Jazz behind the Iron Curtain provides more of an empirical and sociological insight into the cultural, social and, above all, the political contexts of European jazz.

However, both publications show the division of European jazz scenes between East and West, and they also deal with the methodological inconsistencies in jazz research and analysis which have precluded an integrated chronological approach to jazz events, personalities and styles.

American theorists have presented different methodological approaches to jazz research. They range from Gunther Schuller’s historical and analytical approach, Mark Gridley’s stylistically-critical approach, through to Carl Emil Seashore’s, Milton Metfessel’s and Gridley’s exact measurements of African-American singers’ and instrumentalists’ specific tones. However, as jazz research in Europe is an incomplete endeavour, the two publications cannot be regarded as fully comprehensive monographs on European jazz.

One of the problems in the research on European jazz is the evaluation of musicians’ contributions to jazz history. American publications emphasize the concept of progress upon which jazz history is evaluated. From the current perspective however, progress – although regarded as the foremost factor – does not appear to be the only one involved in jazz development. Especially since the death of Miles Davis, the concept of progress has become very uncertain and changeable. However, for the further development of jazz, a respect for the genre‘s traditions is essential as it encourages musicians to preserve the older jazz styles and maintain an authenticity.

Besides progressiveness, the innovative development of the previous styles’ elements is equally important to the future of jazz. Some innovative possibilities have already appeared in the groundbreaking projects of such outstanding personalities as Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, John Coltrane and Miles Davis even so their contribution to jazz history has groundbreaking importance. For the success of jazz amongst audiences, creative musicianship, musicality, jazz enlightenment, advocacy and popularization are also vital. Only with such musical elements and activities is it possible to achieve further characteristics and original jazz expressions.

At this point, we speak of historiography where progress is regarded as the highest ideal, whilst innovations, creative searches, inventions in new combinations or standard productions are treated as lesser ones. Progressive, new or groundbreaking jazz productions seem not to be following the patterns of previous development. The appreciation of progressive, new or groundbreaking jazz albums also depends on artists’ and audiences’ abilities to grasp the critical moment, and recognize the music’s continuity and topicality. However, progressiveness also depends largely on the artists’ abilities not only to compose progressive pieces but to promote them successfully to the audience as well. These qualities are demonstrated by such personalities as the Slovak jazz singer Peter Lipa (b.1943) and the Czech-Slovak-Australian jazz pianist Viktor Zappner (b.1936).

Similarities and Diferencies – Peter Lipa and Viktor Zappner

Both artists have a number of characteristics in common, especially the flair for innovative jazz and finding new combination possibilities, even though both were constrained by the conditions of their time. Viktor Zappner (b. October 11, 1936 in Trutnov) is an Australian jazz pianist of Czech-Slovak origin. He was already using a modal approach in 1962 by transforming the Lydian and Mixolydian intonations of central European folk music into his compositions. However, in Czechoslovakia in the 1960s when there was little interest in jazz, Zappner was an unknown pianist. His music did not become appreciated until after his emigration to Tasmania (Australia) in 1978. He discovered the essence of modal jazz and has popularized it amongst the local Tasmanian public. For his endeavours, Zappner was honoured as the Tasmanian Local Hero at the Australian of the Year Award 2012.1

Peter Lipa has transformed the specifics of the Slovak language into Slovak jazz songs and has developed a blend of soul jazz with a blues and funky style. Since the 1980s, Lipa has popularized jazz amongst the general public and arranged events that have made his name synonymous with jazz. He has organized Slovakia’s major jazz festival, the Bratislava Jazz Days, since its beginnings in 1975 until the present. He has also been the President of the Slovak Jazz Society since 1989.

Zappner founded the Jazz Action Society North-West Tasmania in 1983 and was its President for 28years. Since 2002 he has been the organizer of the annual Devonport Jazz Festival which helped to promote Devonport as an important jazz town in Australia.

Viktor Zappner

In 1962, Zappner wrote the song Good Morning, Mr. Sallinger, but renamed it Huon Pine a few years after having arrived in Australia in order to express his admiration for the beauty of the Tasmanian landscape.2 Good Morning, Mr. Sallinger was performed at Súťaž tvorivosti mládeže (the Youth Creativity Competition Czechoslovakia) in 1963 by the trio of Viktor Zappner (piano), Tibor Platzner (bass) and Jozef “Dodo” Šošoka (drums). The piece was received with such acclamation that Zappner has been offered an opportunity to study composition at the Academy of Music in Prague, but he did not take it. In 1992, Huon Pine was recorded on the CD Tasmanian Jazz Composers – Volume One3 with Zappner on piano, Nick Haywood on bass, Adrian Cunningham on flute and saxophone, and Allan Browne on drums. In 2006 the composition was performed live in Burnie, where the composer wittily remarked: “The composition has no beginning and no end, as in love”, implying that it has no tonal center.

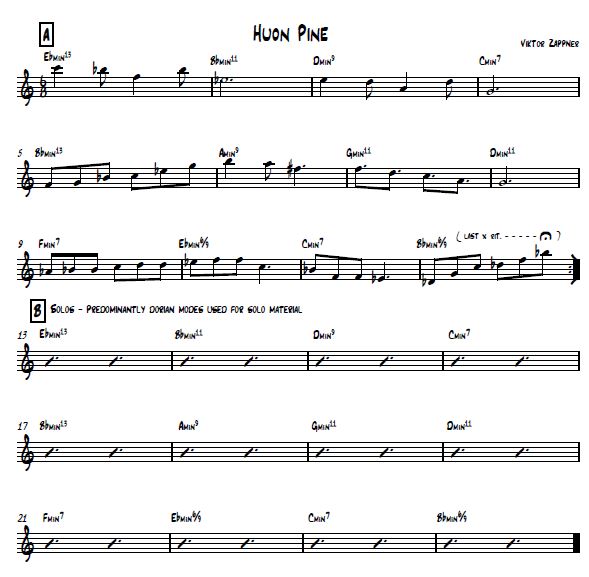

Example: Huon Pine

Huon Pine is based on a two-bar melodic motive composed of the fifth, the fourth, the second and the unison omitting the third (the Dorian mode in E♭ in the first bar, and B♭ minor 11 chord in the second bar). In the third measure the motive is transposed down by the minor sixth. This obscured anchoring in the tonal center, confirms the shifting from E♭ the Dorian mode in the first bar to D Dorian in the third bar, then to B♭ Dorian in the fifth and A Dorian in the sixth measure to G Dorian in the seventh and the eighth bars. Skipping the third in the principal melody allows shifting of the tonal centre to continue. Although the minor third is eventually heard in the F Dorian mode in bar 9 and in the C Dorian mode in bar 11, the motive in the twelfth bar contains several sequences of the interval fourth (D♭ to G) confirming B♭Dorian mode.

In the first eight bars Zappner used the relationship between the authentic E♭ Dorian mode and its plagal variant B♭ Aeolian mode (natural minor); another relationship occurred from bars 9 to 12 the B♭ Dorian mode and its plagal variant f (Aeolian or minor scale) were used. The use of the melodic structure built of the moves of fourths and seconds is close to Thelonious Monk’s musical thinking.

Zappner followed George Russell’s 1953 modal system which had been adopted in American jazz by Miles Davis’ album Kind of Blue as late as 1959. However, the relationships between the chords in Huon Pine are built on a sequential move by the seconds (Dmi9, Cmi7, B♭mi13, Ami9, Gmi11 in bars 3 to 7) which shows Zappner’s original approach.

Huon Pine’s subtle melodic structure is close to Flamenco Sketches by Miles Davis in his album Kind of Blue. However, Zappner’s composition reminds Slovak folk melodies, which are typically based on Lydian or Mixolydian modes. Mixolydian upper tetrachord is identical with Dorian mode. Since the piece was written in 1962, this means that Zappner was using jazz modality in the former Czechoslovakia before or at least at the same time like Jan Johansson did in Sweeden. However, Zappner’s projects were not appreciated at the time, although this musical sound was later regarded as a Manfred Eichner ECM sound.

Peter Lipa

Peter Lipa (b. May 30, 1943 in Prešov) emerged on the musical scene in 1967 as a member of the blues band Blues Five. For political reasons he did not record his first profile LP Moanin’ (Neúprosné ráno) until 1983. From this LP, I have chosen for analysis the piece Kamarátka samota4 composed by Peter Breiner with lyrics written by Tomáš Janovic and Peter Petiška. The English version is known as Me and My Friend Miss Lonelyhearts.

The song’s lyrics appeal to the audience through the connections with the Miss Lonelyhearts column for lonely young people in a prominent American magazine. A similar column also existed in the Czechoslovak popular youth magazine Mladý svět (The Young World). Me and My Friend Miss Lonelyhearts was inspired by lonely people’s letters to Mladý svět (The Young World).5

Example: Me and My Friend Miss Lonelyhearts

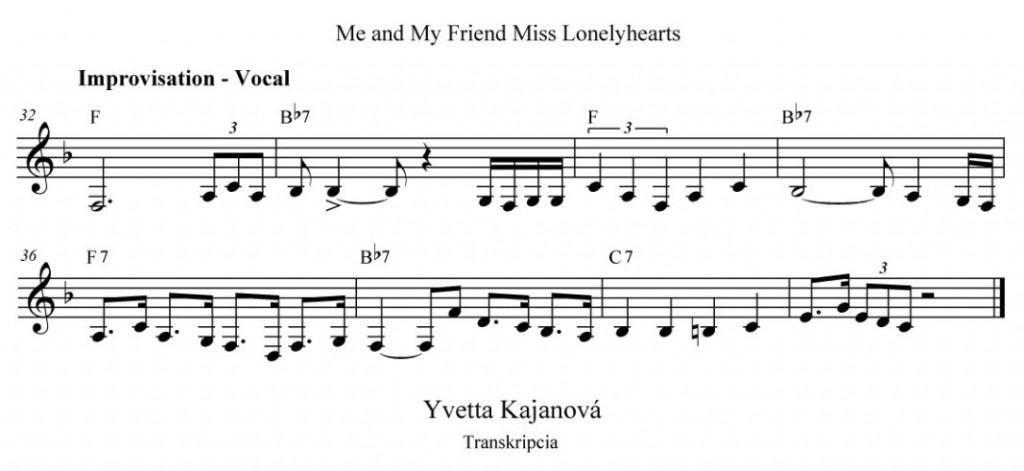

The composition is characterized by the blues key and its alternations with the major and minor keys. This is evident in the first six bars of the introduction, where alternations between F7 chord and Fmi7 chord occur. Alternations also occur at the beginning of section A emphasing the F major key base in the melody (bar 9) and the melody’s sudden transition into the minor third of B♭7 chord in bar 10. The whole piece is written in F key, with part A being in F major key (bars 9 and 11) and, in section B, initially d minor (from bars 19 to 22) changes into f minor (from bars 23 to 30). The eight-bar introduction advances in F blues key with F major dominant in C 7 chord in bar 8 as a preparation for the melody’s F major key in part A. The symmetrical musical form itself (the eight-bar introduction, 8+8 bars in part A, 4+4 bars in the first section of part B and 8+8 bars in the second section), together with the blues tonality correspond with a soul style. The rich phrases dotted rhythm with syncopations and triplets correspond with a soul jazz style too. The transitions between the keys indicate Peter Breiner’s clever use of the functional harmony and classical principle of modulation. The modulation together with the inputs of the bass guitar, using call and response, is an excellent base for the funky style. From here, there is only a small step to the use of groove bass guitar and slapping. In this respect, Peter Breiner’s Me and My Friend Miss Lonelyhearts represents an innovation in blues, soul and funk styles.

Lipa, in his scattting improvizes only on themes of section A, but, according to funk style, chooses only vamp from the harmonic scheme with repeated F and B7 chord followed by C7 and F chords.

Example: Improvisation

The Czech bass guitarist, Vladimír “Guma” Kulhánek, had already used a fretless bassguitar in 1980.

Considering that Me and My Friend Miss Lonelyhearts was recorded in 1983, it had already shown a connection with world jazz development not only in its bass guitar interpretation, but also in its fusion of soul, funk and blues in the singing and in the composition. The approach to the harmony – the duet between Vladimir Kulhánek’s bass guitar and Peter Lipa’s vocal part without any harmonic instrument – was typical of the time, with the bass guitar being the dominant solo instrument and adding rhythmic innovations such as glissandos, melodies and slaps. Jaco Pastorius began to use the fretless bass guitar in Weather Report in 1976, so Peter Lipa and Vladimir Kulhánek’s approach was quite timely.

Breiner’s composition was released in both Slovak and English versions; the lyrics for the English version were translated by Ondřej Hejma. The specifics and different rhythm of the Slovak language compared with rhythmically more flexible English jazz phrases require the jazz singer to have a well-developed feel for rhythm. Ondřej Hejma, when translating the Slovak lyrics into English, had these specifics in mind and he used appropriately the number of sylabusses while translating them to the English.

The match of the music with the rhythm of Peter Petiška and Tomáš Janovic’s lyrics, the classical beauty of blues and soul combined with Peter Breiner’s funky style, and Peter Lipa’s expressive rhythmic phrasing was an interpretation that found wide acceptance with the general public. The predominance of Peter Lipa’s rhythmic feeling over his melodic feeling substantially contributed to his public appeal.

Me and My Friends Miss Lonelyhearts

1. Me and my friend Miss Lonelyhearts

We make one simply perfect pair

And every time she comes my way

I feel sadness she can share

2. Me and my friend Miss Lonelyhearts

I’ve known around the neighbourhood

But still when she is in my arms

Something inside don’t feel so good.

Chorus: Maybe. And I will never know

if she is real or not

Maybe, another stranger would and will what I’ve got

Maybe, she’ll never understand why every day is the same

Maybe, she’ll take me by the hand and we can start again her

game. (“we can start again and again”)

3. Me and my friend Miss Lonelyhearts

We make a very happy pair

We’re watching TV when she is low

Sitting beside me in her chair.

4. She tells me stories of her life

When there is nothing else to do

But still when our day is done

I can’t help waiting for someone new.

Conclusion

Peter Lipa and Viktor Zappner are not highly-awarded jazzmen with portfolios of ground-breaking contributions to world jazz. But they had the flair for innovative jazz and for finding new combinations, new possibilities, even though both were constrained by the circumstances of their time.

Zappner promoted Tasmania on the Australian jazz scene and brought modality to that part of Australia. Through his fusion of modality with postbop elements and free jazz, Australian audiences discovered European modal musical expressions. Zappner also introduced his audiences to Swedish musician Jan Johansson, who was previously unknown in Australia.

Jazz in Slovakia without Peter Lipa’s vocal art would definitely be poorer. Lipa’s ability to intelligently interpret all the characteristics of jazz phrasing into Slovak language, and his synthesis of Slovak and English intonations with typical blues melodic structures were publicly recognized. Additionally, Peter Lipa’s and Viktor Zappner’s contributions to jazz included a numorous activities, which had been popularised. Without them the general public would not accept jazz as a new artistic form.

Notes

- “On 21st November 2011, I went with my wife to Hobart to attend the Australian of the Year Award Recipients’ ceremony. In any case, we did not expect to win anything. When the Prime Minister announced my name as the winner in the ‘Local Hero’ category, I was absolutely shocked… Finally, only 32 candidates were left. The four finalists were announced in Canberra on 25th January 2012 in Parliament House in the presence of the Governor General and the Prime Minister. The presence of a jazz musician among such nominated personalities in the final round was rather eccentric, but that’s Australia.” [From personal correspondence with Victor Zappner, March 2012.]

- Huon pine trees grow in Tasmania and some may be up to 3000 years old.

- North Hobart, Tasmania: Little Arthur Productions, LACD 01, 1992

- (My Girlfriend Loneliness), 9115 1460, Opus 1983.

- From personal correspondence with Peter Lipa, January 2013.

Bibliography

Carl Dahlhaus: Analyse und Werturteil, Musikpädagogik, (Analysis and Evaluation), Forschung und Lehre 8. Schott’s Söhne, Mainz 1970.

Luca Cerchiari, Laurent Cugny, Franz Kerschbaumer: Eurojazzland. Jazz and European Sources, Dynamics, and Contexts, Northeastern University Press, Boston 2012.

Mark Gridley: Jazz Styles. History and Analysis, Sixth ed., Prentice Hall, New Jersey 1997.

Gertrud Pickhan, Rüdiger Ritter: Jazz behind the Iron Curtain (2009), Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2010.

Gunther Schuller: Early Jazz: Its Roots and Musical Development, Oxford University Press, New

York – London 1968.